Something about the modern world is profoundly out of whack. But what?

Pretty much everyone understands that powerful new information technologies are part of the story. Beyond that, though, opinions diverge. For example, liberals and conservatives each favor narratives that highlight the biases and transgressions of the other side. “We’re not poisoning the infosphere,” we think; “they are.”

Let’s take a break from such polarizing narratives, for a few facts tell a deeper tale. In 2006, the attack on the World Trade Center was five years in the past. George W. Bush was president, Italy won soccer’s World Cup, and Pluto suffered the indignity of being demoted to a dwarf planet. Google bought YouTube, Jack Dorsey launched Twitter, zero percent of the world’s population owned a smartphone (they didn’t exist yet), and the average person spent just one to two hours per day online.

Collectively, the world’s 6.6 billion people spent about 400 billion person-hours online that year. (Interested in the math? Back then, about 1.1 billion people used the internet and averaged about 1 hour/day online. Over 365 days/year, that comes to a total of 401.5 billion person-hours/year.) Seem like a lot, right? It was, but the average person was spending about fourteen waking hours per day not online. Put differently, the human experience was overwhelmingly “irl.” (That’s “in real life” for my fellow boomers.)

Then, in 2007, Apple launched the world’s first smartphone. 17 years later, 5-7 billion of us own one. And day after day, the average smartphone user racks up almost six and a half hours online. Together, that comes to an annual total of almost 14 trillion person-hours online. (6B people x 6.5 hours/day x 365 days/year = 14.2T person-hours/year.) Year after year, we add another 10 or 15 trillion person-hours to our species’ cumulative total. Now that’s a lot.

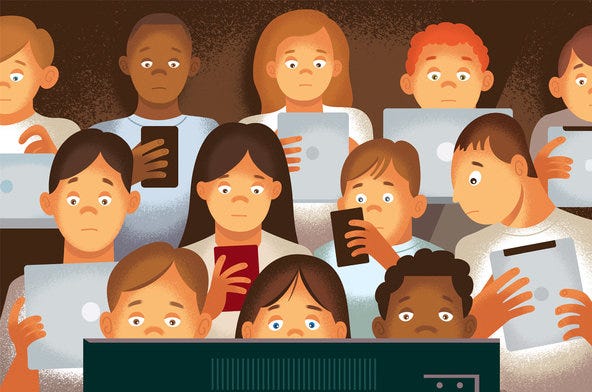

Consider what this means: in just 17 years, we’ve built an information environment that siphons a huge percentage of human attention away from “irl” activities. We used to spend most of our time with real people, building real trust within real communities. We shared food and bought each other drinks. We talked, listened, and offered solace. We played games together, smiled and laughed. We made real friends and felt real belonging.'

Now? Not so much.

I’m talking, here, about a massive reallocation of human attention: a historically unprecedented shift that occurred in less than a generation. And much of it has come at the expense of activities that build trust.

…social media platforms use sophisticated algorithms to maximize “engagement”—a euphemism for time spent on-platform.

Sociologists are raising the alarm about declining levels of trust. Their studies show that we’re less prone to trust the media, our governments, scientists, corporations, legal systems, and even democracy as an ideal. When asked “Can most people be trusted?”, we’re less likely to answer “Yes.”

So: who did this to us? Arguably, we did it to ourselves. We opted in. We bought smartphones and started carrying them everywhere. We came to rely on them and allowed them to monopolize more and more of our attention. In essence, we plugged our brains into the internet and did so voluntarily.

But there’s more to the story. Understanding the value of human attention, tech companies built huge machines to capture it. They worked out how to capitalize on the social capital that friendly people build up over time. (That’s what social media platforms do: capitalize on our evolved knack for making friends.) These companies learned that some information has viral properties – a pronounced tendency to propagate through networks of linked minds, captivating and amusing people.

And sometimes, outraging or radicalizing them.

These companies let other people produce cool memes; then they help the most infectious of them go ultra-viral. This has given countless obscure people 15 minutes of fame. But the bigger story involves pay-to-play fame: pay Facebook to “boost” your content and it will feed it, in greater quantities, to other Facebook users. If you’re Elon Musk, just buy a social media platform and tell the engineers to expand the reach of the views you like, while quietly suppressing the views you don’t.

Back to our story: social media platforms use sophisticated algorithms to maximize “engagement”—a euphemism for time spent on-platform. They taught a bunch of machines to continually improve their capacity for attention capture. In essence, their engineers worked out how to mesmerize millions and keep them glued to their screens.

Ever doom-scrolled for an hour, then wonder where that hour went? Ever hated yourself for doing so? That’s what it’s like to be under the spell of the new engines of mass hypnosis.

The trends aren’t promising. In the United States, the average adult now spends about twelve and a half hours per day consuming media of various kinds. We spend about half of our waking hours – about eight per day – consuming digital media alone. Year after year, that number keeps rising, and the latest phenomenon – TikTok – is taking digital addiction to another level.

We’re also opting for bespoke realities: media diets that tell us what we want to hear, filter out stuff we don’t want to hear, and teach us to despise those who see the world differently.

How much longer can this go on? What will happen when our rootedness in a shared reality ceases to afford enough common ground? When the digital din drowns out the centering call of facts and truth – when the falcon cannot hear the falconer – how can the center hold?

Will mutual tolerance give way to resentment and grievance? Will respect give way to hatred and violence? Will “mere anarchy be loosed on the world”?1 The possibility is all too real.

In a world like this, is it any wonder why we’re suffering an epidemic of loneliness? Any surprise that anxiety and depression are on the rise? Any surprise that polarization levels have spiked? Any mystery why democracies all over the world are in trouble? Of course, people are struggling to thrive in the world we’ve built: when all eyes and minds are glued to screens, the true sources of resilience—connection, purpose, and belonging—become hard to find.

In coming installments of the Mental Immunity Substack, we’ll look at solutions. For now, we’d do well to dwell on the gravity of our predicament. Soon, we’ll muster the insight and courage to act. Until then, please consider supporting the Mental Immunity Project with your tax-deductible contribution.