In this edition of our What Works to Build Mental Immunity series, we collaborated with Glenn Skelhorn, director of The Thinker, a not-for-profit Community Interest Company that empowers minds and communities of the Liverpool area through discussions and thinking workshops. Glenn has years of experience in practicing philosophy with younger students and with community members outside of traditional classroom settings. We are so grateful for his invaluable assistance with writing this piece. We encourage you all to follow The Thinker CIC on Facebook and Instagram.

One way to build mental immunity is by fostering a community of inquiry. Written about in Mental Immunity, communities of inquiry are united by a shared curiosity and collaborative search for truth. This concept comes in large part from the community of philosophical inquiry (CPI) method of the Philosophy for Children (P4C) movement. CPI is an educational method developed by the late co-founders of the Institute for the Advancement of Philosophy for Children (IAPC) at Montclair State College, Matthew Lipman and Ann Margaret Sharp1. Lipman and Sharp pioneered CPI/P4C as an educational approach whereby students engage in moderated philosophical dialogue, helping them develop critical thinking, reasoning, and collaboration skills. By encouraging their innate curiosity, this method nurtures student’s intellectual autonomy and comfort with uncertainty, which are key to lifelong learning. The rest of this article will delve into this pedagogical approach.

The Method

Ideally while sitting in a circle or horseshoe shape to aid in discussion and listening2, a typical session employing the Community of Philosophical Inquiry method would involve the following seven (or six) steps.

1. Starter Activity (Optional)

Try this to stimulate interest and engagement. Options include asking a "Would You Rather" question, such as “Would you rather wrong someone or be wrong by someone? Why?”3 Another example is a "must have, could have" exercise. For example, ask “What properties must something have to be considered a bike?” Some sort of thinking activity can help “get the gears turning” but is not necessary if time is limited.

2. Stimulus Material

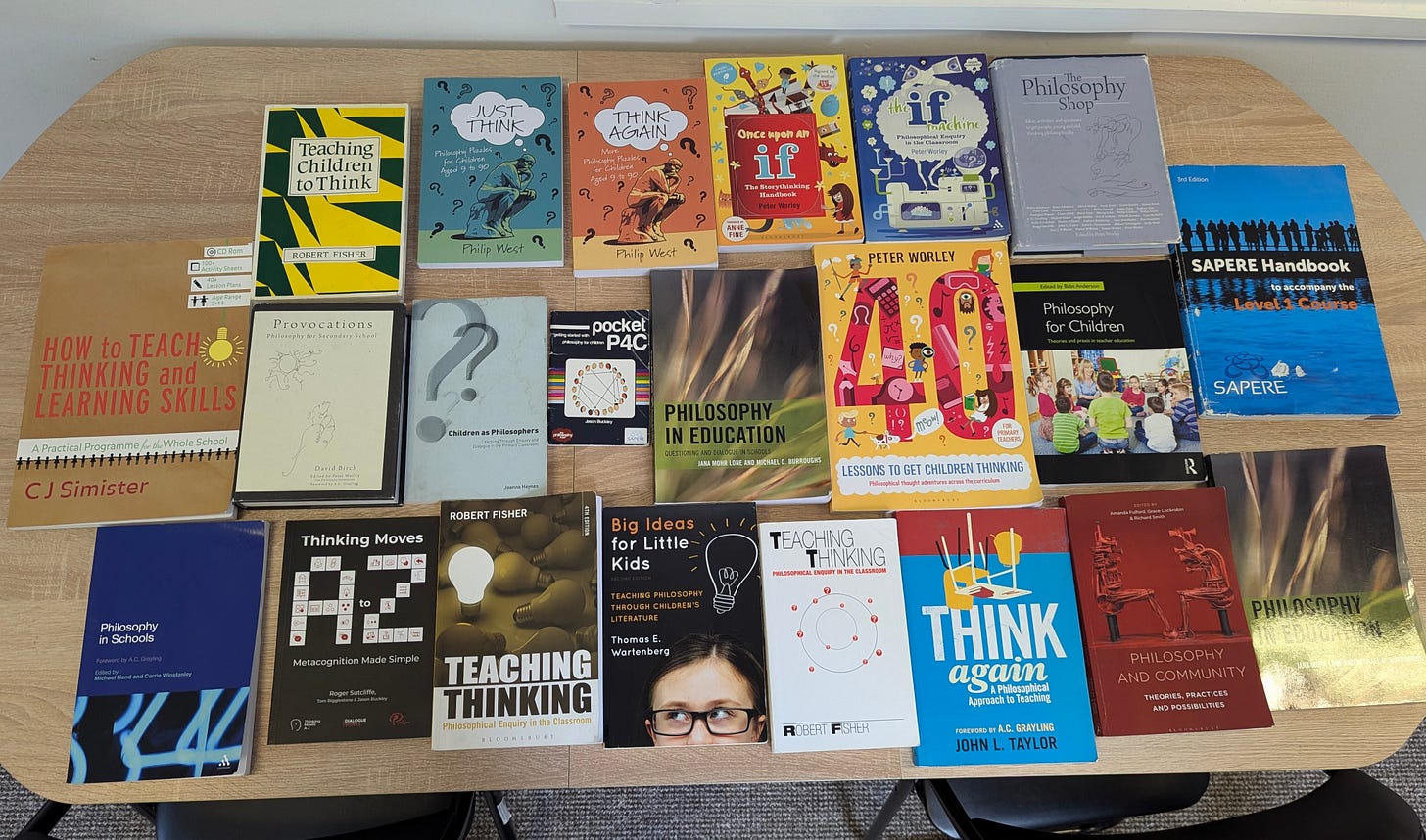

The inquiry must begin with a stimulus material. This can be anything from an object to a story. The chosen stimulus should be intriguing yet open-ended to avoid focusing the discussion too narrowly. Resources like The Philosophy Shop or Provocations can provide useful materials. The stimulus acts as a hook, sparking curiosity and prompting thoughtful questions.

3. The Question

A key element of CPI is generating a philosophical question from the stimulus material. This question should be broad enough to invite diverse perspectives and deep enough to require thoughtful consideration. The goal is to avoid questions with straightforward answers and instead foster discussion that encourages critical thinking. The teacher (or discussion leader/facilitator) can decide what this question is beforehand.4

4. Thinking Time

Students are given time to reflect and write down their thoughts and reasons. This quiet period helps them organize their ideas clearly and prepares them for the ensuing discussion.

5. Small Groups and Pairs

Students first share their thoughts in smaller groups or pairs. This stage allows them to articulate their ideas in a less intimidating setting. Encourage students to be polite and respectful when challenging each other's viewpoints. Facilitate by circulating, stimulating discussion, and reminding students of the inquiry's collaborative spirit.

6. Whole Group Inquiry

The class comes together to share their insights in a whole group discussion. Only one person should speak at a time, and students must raise their hands to participate. These rules should be made clear from the outset. The teacher should facilitate by ensuring balanced participation, summarizing main points, keeping track of the student queue, and gently guiding the conversation as needed. This stage can be challenging, requiring teachers to be attentive and supportive, particularly for shy students.

The group inquiry process is perhaps the most important part, but also the most unpredictable. Occasionally, you may need to break back into smaller groups if too many hands are raised and there’s not enough time to effectively wrap up the discussion. This ensures everyone has a chance to at least share their thoughts before ending the session.

7. Final Reflection

The inquiry should conclude with a reflection session, where students individually summarize the discussion, consider if and how their views have changed, and reflect on the inquiry as a whole. This metacognitive step reinforces the value of being open to changing one's mind and promotes self-awareness in thinking.

This worksheet can be used to help guide the process outlined above.

Additional Notes and Considerations

Importantly, this method is not a silver bullet. It works best when students or group members are accustomed to this collaborative model, which can take some practice and experience. So don’t give up on it if it doesn’t go as you expected the first, second, or even more times. With more practice, it should become more and more useful. The model should be adaptable to serve the needs of the inquiry, but it should not be a free-for-all discussion that turns into an unproductive debate or untamed argument.

To prevent them from becoming chaotic and counterproductive, in addition to following the method outlined above, CPI discussions must be rooted in fundamental values of kindness, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity. Teachers and leaders can benefit greatly from understanding the theoretical foundations of CPI to implement it effectively, so we highly recommend reading into this topic more if you’d like to work on implementing it in your classroom, community, or organization more regularly.

By fostering communities of inquiry, educators can foster classrooms where students learn to ask meaningful questions, engage deeply with ideas, and develop the critical thinking skills essential for navigating an increasingly complex world. Finally, communities of inquiry need not only be cultivated in classroom settings; Glenn et al at The Thinker CIC can speak to this.

Learn More

Young Plato - Official Trailer - Documentary about a primary school in Belfast that employs a philosophical approach to education to counteract the negative cultural influences that many of the students face in their lives outside the classroom.

The Pedagogy of the Community of Philosophical Enquiry as Citizenship Education: Global Perspectives on Talking Democracy into Action coming soon from Routledge

This post is part of our “What Works” series for educators and researchers.

We are open to incorporating feedback into these modules before we publish them on our website. Please comment on this post to provide suggestions. We’re particularly interested in additional applications, resources, and readings. All constructive feedback is welcomed. Thank you!

For all the modules in one place, visit our What Works to Build Mental Immunity Website page! See what’s to come and download PDF versions of these modules.

Inspired by the works of Charles Sanders Peirce and John Dewey, their method emphasizes the importance of a collaborative thinking community where intellectual autonomy is nurtured.

Although it’s paywalled, this essay may be of interest to anyone looking for a deeper dive into this topic: Lipman, Dewey, and the Community of Philosophical Inquiry.

Here’s an excerpt from the abstract: “This paper explores CPI as a concrete application of John Dewey's educational theory, which posits a drive towards the reconstruction of habits—including, and perhaps primarily, the reconstruction of habits of belief—as an ongoing result of the dialectical relationship between our current habits and what he calls “impulse,” and works to overcome through dialogue the gaps Dewey identified between child and curriculum, the “psychological and the logical,” and ultimately, between child and adult.”

This is emphasized here: P4C: what, why and how?

Plato’s Republic

This is a modified version of the traditional method whereby students democratically select the focus question, which has the benefit of giving the students more power over the process, but time constraints often make it is preferable for the question to be provided by the facilitator.